TL;DR — Key Takeaways

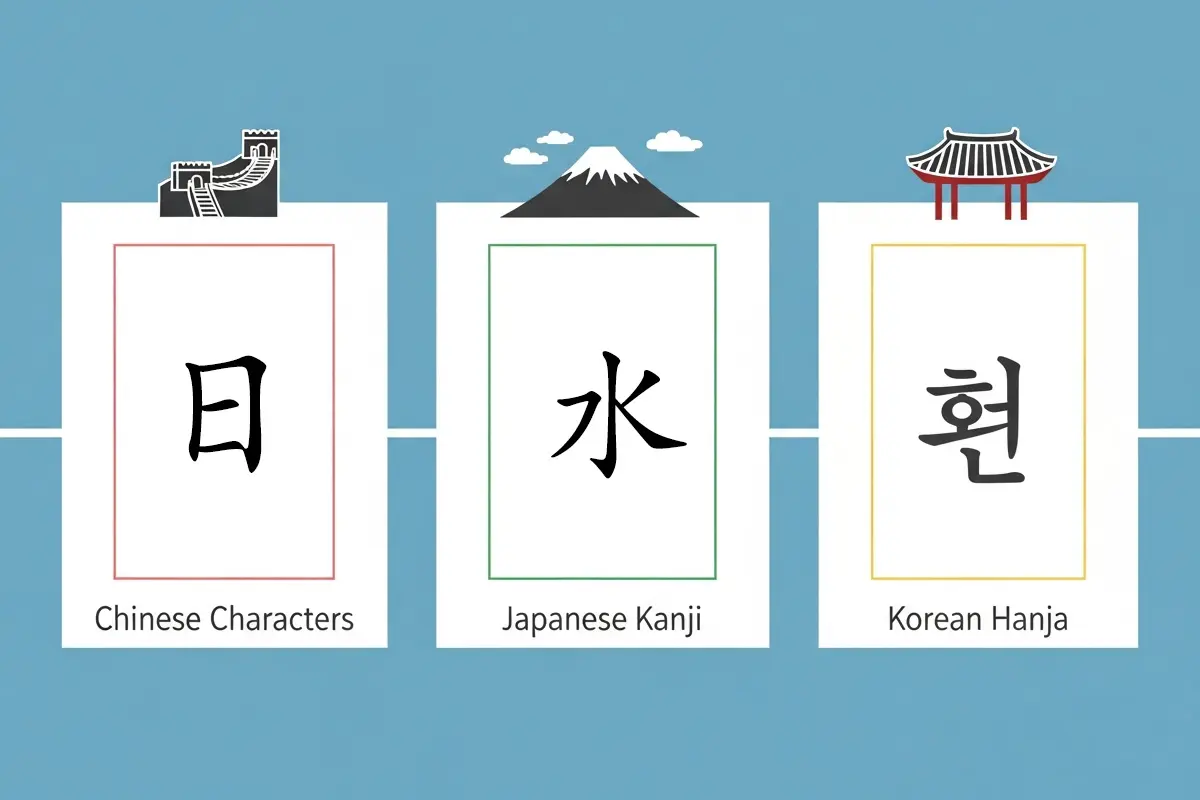

- Chinese characters (Hanzi) are the original logographic writing system developed in ancient China.

- Japanese Kanji were borrowed from Chinese characters but adapted to fit Japanese grammar and pronunciation.

- Korean Hanja also came from Chinese writing, but were gradually replaced by the native Hangul alphabet.

- All three share visual similarities, yet differ in pronunciation, usage, and frequency today.

- Understanding their relationship helps language learners connect East Asian linguistic history and modern communication.

What Are Chinese Characters (Hanzi)?

Chinese characters — known as Hanzi (汉字) — are the world’s oldest continuously used writing system. Originating around 1200 BCE from oracle bone inscriptions, Hanzi evolved through centuries into thousands of standardized symbols representing meaning rather than sound.

Each character typically corresponds to a single syllable and conveys both a phonetic and semantic component. For instance:

- 日 (rì) means “sun” or “day.”

- 木 (mù) means “tree.”

- 林 (lín) combines two “trees” to form “forest.”

Unlike alphabetic systems, Hanzi is logographic — meaning words are formed by combining individual characters rather than letters. As explained in Britannica’s overview of Chinese writing, this structure allows multiple dialects to share the same written language even if spoken forms differ.

If you’re curious how these ancient forms transformed over time, see Origin and Evolution of Chinese Characters, which traces their journey from oracle bones to modern writing.

Today, Chinese writing exists in two forms:

- Traditional characters (繁体字) — still used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

- Simplified characters (简体字) — standardized in Mainland China in the 1950s to promote literacy, as discussed in Difference Between Traditional and Simplified Chinese.

How Did Japanese Kanji Develop from Chinese Characters?

Japanese Kanji (漢字) originated when Chinese writing entered Japan between the 4th and 5th centuries CE via Korea and Chinese scholars. Initially, Chinese characters were used to write classical Chinese texts in Japan. Over time, the Japanese language adapted these symbols to represent Japanese words and grammar.

Early Japanese scribes created hybrid readings:

- On’yomi (音読み) — the Chinese pronunciation of a character.

- Kun’yomi (訓読み) — the native Japanese reading assigned to the same symbol.

For example:

- 山 means “mountain,” read as san (On’yomi) or yama (Kun’yomi).

- 水 means “water,” read as sui or mizu.

Because Japanese grammar is agglutinative — relying on inflections and particles — Kanji alone couldn’t express the full language. Two additional scripts, Hiragana (ひらがな) and Katakana (カタカナ), later evolved to represent grammatical endings and foreign sounds.

For learners exploring script combinations, the article AI Kanji: The Meaning and Writing of 愛 (Love) in Japanese offers a modern example of how Kanji integrates with other writing systems.

Today, Kanji remains a core part of Japanese literacy:

- About 2,136 Jōyō Kanji are officially used in daily life and education.

- Newspapers, signage, and literature still blend Kanji with Hiragana and Katakana.

What Is Korean Hanja and Why Is It Rare Today?

Korean Hanja (漢字) refers to Chinese characters used in the Korean language. For over a millennium, educated Koreans wrote exclusively in Classical Chinese, known as Hanmun (漢文). Korean Hanja were essential for government, literature, and scholarship throughout the Goryeo and early Joseon periods.

In 1443 CE, King Sejong the Great introduced Hangul (한글) — a phonetic alphabet designed to represent Korean sounds accurately. Hangul’s simple and scientific design made literacy accessible to everyone, gradually reducing reliance on Hanja.

Even so, Hanja continued in academic and official contexts for centuries. You can still find Hanja:

- On historical monuments and legal documents.

- In newspapers and academic journals in South Korea.

- In personal names (most Korean names have Hanja roots).

Today, North Korea has completely abolished Hanja, while South Korea teaches it at a limited level to preserve cultural literacy. To understand Korean pronunciation patterns that evolved after Hangul replaced Hanja, see Seoul Korean Pronunciation: A Complete Guide.

Comparison Table: Hanzi vs Kanji vs Hanja

| Feature | Chinese Hanzi | Japanese Kanji | Korean Hanja |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Ancient China (~1200 BCE) | Imported from Hanzi (~4th century CE) | Imported from Hanzi (~1st century CE) |

| Writing System Type | Logographic | Mixed (Kanji + Kana) | Historical Logographic |

| Current Use | Main script (Simplified/Traditional) | Widely used with Kana | Rare; limited academic use |

| Example Character | 人 (person) | 人 (hito or jin) | 人 (in) |

| Number of Common Characters | ~3,500 | ~2,136 (Jōyō Kanji) | ~1,800 (historical) |

| Reading System | One reading per character | Multiple readings | Based on Chinese pronunciation |

| Modern Replacement | None | None | Hangul (한글) |

This comparison shows that while all three systems share a common root, they diverged to fit their linguistic environments — Chinese for meaning, Japanese for flexibility, and Korean for accessibility.

Are Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Writing Systems Related?

Yes, but not genetically — rather through cultural transmission.

All three writing systems trace back to Classical Chinese as a scholarly and diplomatic language across East Asia, known historically as the Sinographic sphere.

However, the degree of adaptation differs:

- Chinese remained logographic, maintaining its own spoken and written forms.

- Japanese incorporated Chinese script but reshaped it through dual readings and kana syllabaries.

- Korean preserved Chinese learning for elite communication before replacing it with Hangul, a native alphabet.

According to linguistic historians, Classical Chinese functioned as a lingua franca that facilitated centuries of communication, scholarship, and cultural exchange between China, Japan, and Korea.

As noted in the research study “Classical Chinese as Lingua Franca in East Asia in the First to Second Millennia CE” by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, this shared literary medium allowed intellectuals from all three civilizations to exchange ideas despite linguistic differences (Read the full study here).

For a deeper understanding of how writing systems shape linguistic identity, the post Best Online Chinese Course: Your Complete 2025 Guide also discusses how modern learners approach Hanzi within today’s digital education context.

Which Is Harder to Learn: Hanzi, Kanji, or Hanja?

The difficulty depends on learning goals and linguistic background.

- Hanzi: Learners must memorize thousands of unique characters. Each conveys meaning and pronunciation but lacks an alphabetic shortcut.

- Kanji: Considered the hardest overall due to dual readings and mixed-script writing. Native Japanese words often have both kun’yomi and on’yomi pronunciations.

- Hanja: Easier to learn conceptually for Chinese speakers, but less practical since Hangul dominates Korean writing today.

| Learner Type | Easiest System | Hardest System |

|---|---|---|

| Native Chinese | Hanja | Kanji |

| Native Japanese | Kanji | Hanzi |

| Native Korean | Hangul (not Hanja) | Hanzi |

| English Speaker | Hangul | Kanji |

For practical purposes, Hangul is the fastest script to master, while Kanji remains the most complex due to polysemy and contextual readings.

Cultural and Linguistic Impact Across East Asia

The shared foundation of Hanzi, Kanji, and Hanja created a pan-East Asian cultural identity centered around Chinese classical thought, Confucian ethics, and literary traditions.

- In China, calligraphy (书法 shūfǎ) remains a revered art form symbolizing harmony and wisdom.

- In Japan, mastery of Kanji enhances literacy and connects readers to classical literature and Zen philosophy.

- In Korea, Hanja links modern Koreans to their historical roots while Hangul reflects national identity and independence.

Together, they form a linguistic triad — a living reminder of how language evolves yet preserves continuity across civilizations.

FAQs: Chinese Characters vs Japanese Kanji vs Korean Hanja

Do Chinese, Japanese, and Korean share the same characters?

They share many characters in origin, but forms and meanings have diverged. For example, the character 学 means “study” in all three, but pronunciation varies: xué (Chinese), gaku (Japanese), hak (Korean).

Why does Japanese have three writing systems?

Japanese combines Kanji for meaning with Hiragana and Katakana for grammar and sound representation, allowing flexible sentence structure.

Does Korea still use Hanja?

South Korea uses Hanja sparingly in academia and names, while North Korea abolished it completely after the 1950s.

Which system should I learn first as a beginner?

If you plan to learn one East Asian language, start with its modern script: Simplified Chinese (for Mandarin), Kana + Kanji (for Japanese), or Hangul (for Korean).